Play Ball!: An Interview with Emily Nemens

Interviews

By Robert Rea

When you think of the Southwest, what works of fiction come to mind? If you’re a fan of westerns, you probably think of books by Cormac McCarthy and Larry McMurtry. Maybe you’re into crime novels, and it’s something by Jim Thompson or Dorothy Hughes. Or it could be the reservation novels of Leslie Marmon Silko and N. Scott Momaday. Whatever your taste in fiction, chances are you don’t think of baseball.

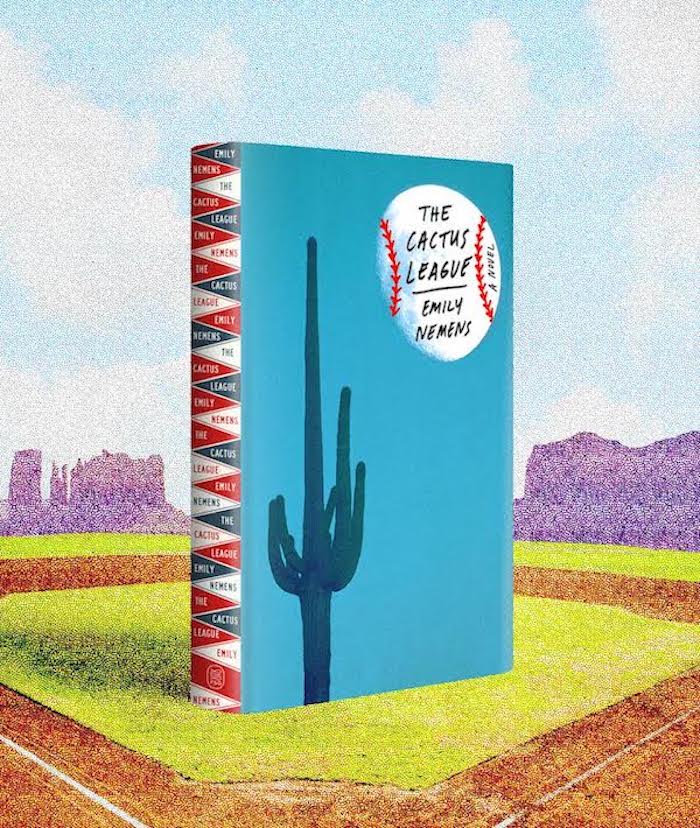

Enter Emily Nemens and her sprawling debut, The Cactus League. A cross-cutting story with an ensemble cast, this is more than a book about home runs and strikeouts. It explores a whole industry, from top to bottom, through a fictional team, the Lions, and their spring-training home in Arizona.

If there is a main character, the Lions’ shiny new stadium-slash-casino is it. Nemens’s novel can best be summed up in the pecking order around the ballpark. There are those at the top—like All-Star outfielder Jason Goodyear and team minority owner Stephen Smith—who are seemingly so successful that they make others nervous. There are those in the middle—a has-been hitting coach, a rehabbing pitcher—hoping to stick around for opening day. Then there are those at the bottom, like Alex, whose mom scratches out a living selling hot dogs, or Tami, an aging groupie who hangs around practice and would give anything to meet a star like Goodyear. The result is an ambitious social novel about today’s sports-entertainment complex.

When she’s not writing fiction, Nemens edits The Paris Review. Somehow, while running a lauded literary magazine, she found time to publish a novel. We spoke over email about being an LSU fan, the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, and the evolution of her new book, out now from FSG.

Robert Rea: Tell us about the origins of The Cactus League. Where did the idea come from?

Emily Nemens: When I moved to Louisiana to start grad school at LSU, I was entirely unprepared for LSU football and the tailgating culture around it. I was fascinated by the phenomenon (it felt like the circus came to town several Saturdays of the fall), excited by the community building that occurred there, but also, as I began participating in it, I became more aware of how problematic it could be. SEC football is not spring training baseball, but I noted the parallels of what can occur when people gather around a locus of spectator sport.

RR: What specific parallels do you see between big-time college football and the story you’re telling in the novel?

Listen, I love school spirit and community, and of course LSU has always been competitive (national champs this year—geaux Tigers!), but those home games also meant a ton of binge drinking and bad decisions, crazy pageantry, and, in the end, the campus would be fairly trashed (though, to the credit of the grounds crew, everything would be put back together by Monday). But that’s a digression.

Here’s the part that carried over to spring training: something felt very off about the idea that these rabid fans—plenty of whom weren’t even LSU students, maybe not even alums, definitely far beyond college age—were so crazy for the team and putting so much pressure on these kids. They were boosters when the games were going well, but also really nasty, mean fans when things went badly. I was fascinated to see how people grafted these big emotions and impossible expectations onto a group of amateur athletes that, frankly, didn’t deserve that kind of pressure. I think that kind of transference happens at spring training, too—a lot of my characters are thinking about their own disappointments and potential salvations, imposing them on this group of athletes who are just trying to get ready for opening day.

RR: Are there other works of fiction about sports that influenced it?

EN: The Throwback Special, by Chris Bachelder, was absolutely brilliant. As you might know, the premise is a group of retired football players reuniting for an anniversary of a big game. The complicated feelings and fragile masculinity on display were fascinating and affirming of the work I was already exploring in early versions of The Cactus League—the character of Michael Taylor, the surly batting coach, has been almost retired and mad at the world since around 2014.

RR: The story circles around training camp for the Los Angeles Lions. Why did you choose to write about a fictional team, rather than, say, the Dodgers?

EN: I wanted control over every aspect of the team, and I worried that using a real team would come with too many strings attached. There are a few real athletes mentioned as reference points, of course, but I didn’t want the clash between artistic license and the facts of a particular team’s structure or organization to distract a reader. At the middle of this project is a world-building exercise, and what’s more fun than building a whole team from scratch?

RR: The book offers a wide-lens view of the sports-entertainment industry. It tells the interlocking stories of an All-Star outfielder, his agent, a hitting coach, a concession worker, players’ wives—who all attend spring training in Arizona. Did you come to this purely as a fan of the game, or did you do some research?

EN: I was a fan first—I’ve been going to spring training since the 1990s, so it was in my blood and muscle memory. But as for writing, I started with the stories, then would hit pause when I encountered something I knew I needed to know more about. I did a lot of reading, watching movies and TV, games and interviews, and consumed tons of sports journalism.

I don’t remember where I read this, but someone said fiction writers research just enough to sound convincing, and that was definitely the case in my work. I had a pretty good eye, eventually, for spotting where something felt thin, underdeveloped, or implausible, and then I’d read a few sports autobiographies or study some historic maps or read about Tommy John surgery until I found the detail I needed, or (more often) the detail that served as inspiration to create the detail I needed. Because I could—it’s fiction!—I took some liberties, stretched some plausibility for dramatic effect and all the rest.

RR: The Cactus League could be called a baseball novel, and yet it’s just as much a book about the pains of growing older and the process of aging. What, if any, in your mind are the connections between the national pastime and the passage of time?

RR: The Cactus League could be called a baseball novel, and yet it’s just as much a book about the pains of growing older and the process of aging. What, if any, in your mind are the connections between the national pastime and the passage of time?

EN: Well, the aging ballplayer is such a trope—thanks, Kevin Costner! I was interested in examining that transition, but wanted to avoid the clichés of it. So I started to think about it obliquely—how all these other people in the orbit of the team are getting older, too. How does it manifest in them? An aging batting coach. A woman who has relied on her looks for two decades. A musician who is becoming redundant because of technology.

I think it’s interesting to consider the aging process vis-à-vis baseball now, as baseball itself is being debated as perhaps being past its prime, or at least its primacy in American spectator sports.

RR: The novel takes place in Arizona. How does the setting inform the story?

EN: Well, watching baseball in March in the desert is a really special thing, and for people who have been to the Cactus League, the title should set the mood right away. There’s something about the air, about the light. But I also was interested in Phoenix, and Scottsdale in particular (which is on the eastern edge of the Phoenix metro) because there are so many elements coming together there: a growing city and a mountain range, historic architecture and new construction, new arrivals and Native American communities who have been there for millennia. As for the desert itself, I like that it can be seen as this restorative place and this menacing terrain. I suppose spring training can be seen the same way.

RR: There are some gorgeous descriptions of the natural environment. How do you see these working for the reader?

EN: When I realized a new baseball stadium was the inciting incident, I started thinking about monuments and monumentality. The construction of the stadium and casino may feel like monuments in the contemporary moment—they are the biggest buildings around—but what about those mountains behind them? Aren’t those bigger still? If the natural world can’t be recognized as monumental against the built environment, well . . . we’re screwed. Reasserting the scale of the natural world, its shifts and evolution, felt necessary to put the current situation in perspective.

RR: The architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright also plays a role. Why did you decide to thread the novel with these references?

EN: Because I love Frank Lloyd Wright! No, actually I was thinking more about monuments and scale, and how those have shifted over time. I found it fascinating, and a helpful orienting detail, that Wright built this monument [Taliesin West] in the desert and he thought he would be entirely isolated. The city encroached on his dream, and the next generation of monuments was something else entirely—much brasher, less thoughtful architecture, monuments that kind of turn their backs on the landscape. What does it say about contemporary society that we got from this inobtrusive, organic modernist icon to cookie-cutter subdivisions and an all-night casino/sports complex? Nothing flattering, I’ll tell you that. In that way, I guess Wright’s work is this slightly moralizing reminder of what the built environment can do, how it can coexist with nature.

RR: Can you tell us what you’re working on now?

EN: Most days I’m thinking about The Paris Review from sunup till after dinner. But I miss writing being a part of my routine, and I’m digging back into some long stories, which are organized around museum objects—kind of the opposite of the ballpark. Except maybe not—instead of the athlete on the pedestal, you’ve got a rare gem or some extinct bird or a marble sculpture. People gather around, and the more people see the piece, the more of an icon it becomes. That’s not so much different than everyone fawning over an All-Star’s performance, is it?

Robert Rea is the Deputy Editor & Web Editor for SwR.

More Interviews