A Much Fancier Dress | An Interview with Jac Jemc

Interviews

By Mesha Maren

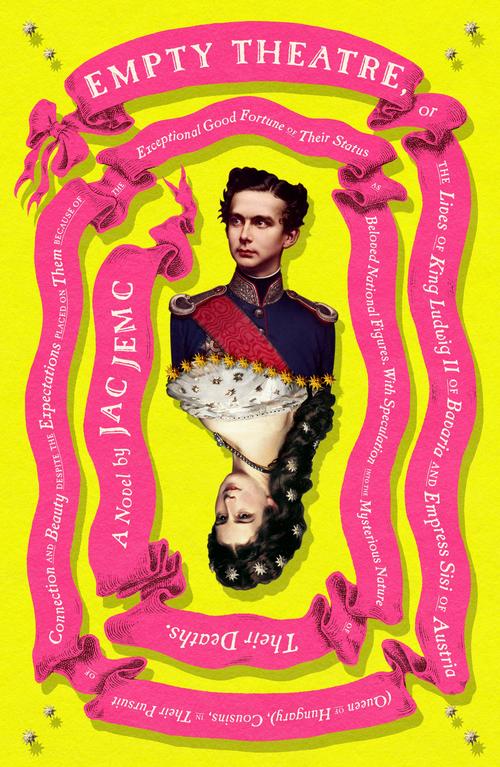

Jac Jemc’s latest novel, Empty Theatre: A Novel: or The Lives of King Ludwig II of Bavaria and Empress Sisi of Austria (Queen of Hungary), Cousins, in Their Pursuit of Connection and Beauty Despite the Expectations Placed on Them Because of the Exceptional Good Fortune of Their Status as Beloved National Figures. With Speculation into the Mysterious Nature of Their Deaths, has a title so long that not even the publisher (MCD/FSG) features it in full on their website. It’s an audacious title for an audacious book, one that’s also intimate, eccentric and as effervescent as reviewers have been saying. The novel follows the lives of King Ludwig II of Bavaria and Empress Elizabeth of Austria, cousins, friends, and icons of the late nineteenth century who died young and left behind magnificent portraits and palaces. I was lucky enough to converse with Jemc over email about Ludwig and Sisi, present versus past tense, genres and research.

Mesha Maren: Empty Theatre is a 464-page book. The epic proportions of this novel remind me of the castles that Ludwig commissioned, buildings that were, in your words, “frothy confections perched on mountains or remotely placed on islands.” Maybe these epic proportions, and the book’s epic title, are also reminiscent of the Wagnerian operas that Ludwig loved. Yet, if my memory serves me correctly, your previous books never topped 200 pages. Can you talk a little bit about what it was like to write a book this big

Jac Jemc: Writing a book of this scope and size was definitely a departure, but that was by design. A previous draft was triple the book’s length at one point. The published version is actually less than 100,000 words. But the chapters are relatively short, which makes the book, by page count, seem longer than it is.

Jac Jemc: Writing a book of this scope and size was definitely a departure, but that was by design. A previous draft was triple the book’s length at one point. The published version is actually less than 100,000 words. But the chapters are relatively short, which makes the book, by page count, seem longer than it is.

Okay, now that I’m done hedging all that: I was excited to write a big book! I knew from the start that the subject matter would demand a little more grandiosity than I’d previously employed, although I do think all of my books could qualify as maximalist. This book is all about the flamboyant details and weird idiosyncrasies of these figures’ lives, so it needed the space to sprawl and mutate, just like Ludwig’s tastes and Sisi’s urge to travel did.

MM: You wrote Empty Theatre, a historical novel, in the present tense. What can you tell me about this choice?

JJ: I worried over this choice a lot. I kept trying to write it in the past tense, but kept reverting to the present. Present tense made the story feel like I was watching something right in front of me, like a car crash. I knew what was going to happen, in what felt like slow motion, but there was nothing I could do to stop it. The present tense felt like it brought the discomfort to the surface for me.

MM: Mary Gaitskill wrote an essay about prose style that my mind seems to return to whenever I read a new book by an author I’m familiar with. She describes a man who worked in a bookstore and asserted that a writer’s prose style was “the ‘inevitable by-product’ of the writer feeling their way through the shape of their creation, through word choices and small decisions as well as big ones.” Gaitskill goes on to say that description in writing can “give words to what is wordless and form to what is formless through creating pictures and images that irrationally make a connection to the deeper body of the story—the viscera or unconscious.”

Can you talk about your relationship to your prose style? Did it shift or not shift as you were telling Ludwig’s and Sisi’s stories.

JJ: This is such a fantastic quote. It says much more succinctly and eloquently something I often try to impress upon my students about the intuitive connections we create as we choose our figurative language and feel out the voice of a piece. One of the first things that excited me about working on a piece of historical fiction was the access research would give me to new words and images. I also felt my narrator’s distance from the action from the start, and decided to embrace that. That distance allowed me to observe and comment on the absurdity and spectacle of these figures who lived lives impossibly different from my own. I think Empty Theatre is a funnier, potentially crueler book than my other novels because of that distance.

MM: Empty Theatre is, on the surface, a very different “kind of book” than your previous books. What are your thoughts on historical novels, on having written a historical novel, on how Empty Theatre is or is not in concert with your other works?

JJ: When I started thinking about this book, I’d recently read Laurent Binet’s HHhH. In that book, Binet recounts the assassination of Nazi leader Reinhard Heydrich by Czechoslovak soldiers, but he also takes as his subject the research and writing of the book itself. A friend had recommended I read it while I was visiting Prague. Although it didn’t sound like something that would typically interest me, I became immediately obsessed with the novel’s voice: funny, self-important, paranoid, troubled by all the expectations that come with working in the genre. I don’t think it’s inaccurate to say that after reading Binet’s story of researching his book, I wanted to create a similar experience and obsession for myself, which is what I ultimately did, whether or not I was fully cognizant of that.

There are so many books I then read and admired and thought about as I was making my own choices: Danielle Dutton’s Margaret the First, Alexander Chee’s Queen of the Night, Kathryn Davis’s Versailles, Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard, and Rivka Galchen’s Everyone Knows Your Mother is a Witch. These were the historical novels that felt like they held real surprises in their form and focus.

And yes, I do think that Empty Theatre is in concert with my other books. It overlaps with The Grip of It in that both books feature architecture as an exterior expression of an internal state. I look back to My Only Wife and see a parallel interest in self-mythologizing and the seed of an attraction to opera with all its pomp and scale. Both books also feature pairs of people who ultimately prove inscrutable to one another. Empty Theatre is wearing a much fancier dress, but it’s the same gal with the same set of anxieties underneath.

MM: I’m very curious about your research process. It seems obvious that you did a lot of research for a book like this. But what exactly was the relationship between your research and your writing? When I saw that Fernando Flores had blurbed your book, it made me think about a conversation I had with him about his idea of writing an “anti-research” novel (Tears of the Trufflepig) where anytime he felt the need to do research, he stopped himself and just made something up. What was your relationship to “truth” during the writing of Empty Theatre?

JJ: I was obsessive about the research. I read a lot of books about these people as a place to start and flagged far too many moments or facts I wanted to include. I tried my very best to make things as accurate as possible in my early drafts, sometimes telling myself I’d go back and fix a thing later. But I’d forget what I’d verified and what needed extra attention. In later drafts, I let myself manipulate the material more. I consolidated some characters and picked which moments were the most emblematic of repetitive dynamics. I didn’t need to exaggerate much, if at all, though. Ludwig’s and Sisi’s lives are just that outrageous, so I never really worried about tarnishing their reputations. The most extreme behaviors in the book are rooted in some “factual” source I found.

MM: Are readers supposed to ask what is true and what is not as they read this novel? I felt compelled so many times to Google certain things, but I held back because part of the novel’s beauty lies in not knowing what’s real and what’s invented.

JJ: Yes! I think readers should ask themselves what’s true and what’s not because it’s so much fun, or at least I think it’s fun when I read novels based on real life. One of my goals for the tone of the book was for it to feel a bit like gossip.

MM: Did you work with a fact-checker? When my novels were in the process of being published, I was shocked to learn that Algonquin Books was using a fact-checker. Why would I need a fact-checker? The books were fictions. But the fact-checker was very helpful with all sorts of obscure moments in the books. It would be fascinating to hear about your conversations with fact-checkers and editors.

JJ: My gosh, I wish I had a fact checker! MCD/FSG agreed with the idea that the book is fiction. I considered hiring one of my own, but there are so many facts to check, I’d have spent most—if not all—of my advance on it. That said, the copy editors were a total dream and helped to catch many small errors and inconsistencies. I tried to do my due diligence in my own research, but there must be moments where I don’t know what I don’t know. I’m bolstering myself for the people who show up to the readings to tell me what I got wrong.

MM: When you received your hardback copies of Empty Theatre, you posted (on Twitter, I think) about how you never really expected to have a hardcover book. You mentioned that you had mentors and teachers who told you how hard publishing is, and it seemed like they thought of your writing as more “small press writing.” “Small press writing” is my favorite kind of writing, but I also understand that it can be thrilling to hold a hardback copy of your own book in your hands. Can you talk a bit about your “writing career” and the twists and turns that have led you to the moment of hefting a hardback of Empty Theatre up in the air?

JJ: Gladly! I feel incredibly lucky to have had the experiences I’ve had in publishing. I agree that “small press writing” is also my favorite kind of writing. I love that two of my books are with Dzanc, who continues to do top-notch work. Coming up with that idea that I didn’t fit into Big 5 Publishing, I’m happy that I’ve never really had to think about sales when I’m writing my books. I honestly don’t think I know how to write something for a wide audience, and I don’t think I could even if I tried. I know what obsesses me in terms of narrative, character, and ideas, and I try to trust those fixations. I work the prose until the voice and language don’t make me cringe anymore. I get strategic about the organization and pacing of the story around the second draft, but that work is more about the shaping and ordering of images and thoughts than it is about plot. I wrote a horror book that horror readers don’t seem to love, but literary readers like okay. I wonder if Empty Theatre will have a similar life in relation to historical fiction, and that’s exciting to me rather than frustrating. I came up with a bunch of “small press writers” who were gradually embraced by Big 5 Publishing, and I feel like I sort of floated in on their wake. I know how much luck is involved in this kind of development, and I don’t doubt the luck will eventually run out. But I’ll just keep showing up, doing my work, and hoping I can find my audience, whatever the size.

Mesha Maren is the author of the novels Sugar Run and Perpetual West (Algonquin Books). Her short stories and essays can be read in Tin House, Oxford American, The Guardian, Crazyhorse, Triquarterly, The Southern Review, Ecotone, Sou’wester, Hobart and elsewhere.

More Interviews