A New Lodestar | The Collected Stories of Peter Christopher

Reviews

By Conor Hultman

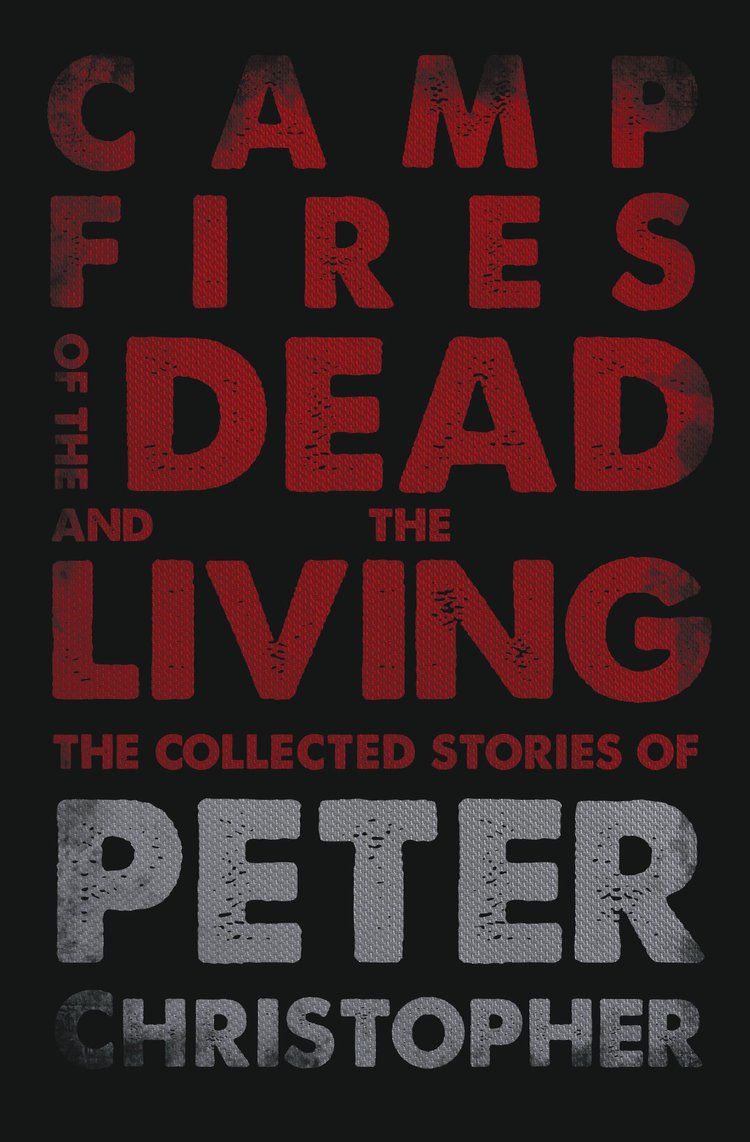

Attention, short story devotees: you will have a new lodestar. Chekov, Coover, Carver . . . Christopher. I don’t know why they all start with C. Don’t read into it. Don’t read Campfires of the Dead and The Living: The Collected Stories of Peter Christopher (11:11 Press) if innovative syntax causes you jealousy. Don’t read it if you’re comfortable with your “voice” or think the English language has been completely mapped. You will be crushed to know that someone else has discovered a new perfect first line: “The flies have found her.”

Do read this book if you need the neural rush that only the best short stories deliver; the kind of story that keeps you desperately chasing the fix from one literary magazine to the next. This book features more than two dozen stories like that—in a row.

The glue that binds a Peter Christopher story is a sense of humor that cons you into a kind of Weltschmerz. You’ll wonder how a story entitled “The Man Who Failed To Whack Off” could go anywhere other than the raucous. An elderly regular to a strip club journeys to a coin-operated booth in the back. The neon signs flash variations on his desire: “LIVE GIRLS, SEE LIVE GIRLS, LIVE GIRLS HERE”; “GAZING LIVE GIRLS, BUBBLE-GUM-BUBBLE-BLOWING LIVE GIRLS, SMOKING LIVE GIRLS.” The girls themselves heckle him like sirens. “Yo, Gramps! Bumpers! Get a load of these garbos, creamers, bonkers, congas, rib-bangers!” But then the signs and strippers converge, our protagonist enters the booth, and this happens:

Mouth-breathing the heat, he tries. The shade un-winds as he pumps faster, as he drops the brass token. Reaching for the token becomes stabbing behind eye: becomes dizziness: becomes sitting down hard: becomes sucking the ammonia smell: becomes sucking the cool floor: becomes suck, suck, suck.

Death and lust; a sober meditation about the end, served in a brightly colored wrapper.

Many of the stories deal with heartbreak. A middling lawyer works up the nerve to call his lost love. A dumpster-diver sees almost as much humanity in stray animals as he does in humans. A man drives his dead uncle’s Impala to smell him again, “his brand of smokes and after-shave.” Christopher manages to make a story about “chicken-sexers” (that is, workers who gender chicks in an industrial coop for two cents per) into something domestic and touching.

Other stories combine comedy and tragedy in equal measure. “Hunger” is framed as the recollections of a cook for death row inmates. He keeps a list of last meals he’s served: “One slat of saltine crackers, peanut butter, marshmallow fluff, ice water”; “Two boxes of sugar frosted flakes, one pint of skim milk, two Snicker candy bars”; etc. A list as morbid to read as it is lunatical in its circumstances. The bulk of the story becomes a letter that a condemned inmate has sent to the narrator, ostensibly to make his last meal request. That letter then turns into a comical description of the murders this individual has committed. “The old man got his with his own .38 after he hollered about me piss-sopping my sheets again,” the text confesses. Later: “Aunt Gert and Aunt Gert’s poodle got popped a little later, Aunt Gert for farting her MILLER HIGH LIFE beer farts, her pooch just for reminding me of me, looking like I felt–hairwise, that is.’ You are lulled into thinking one, just this one story, is mostly for laughs. But then you encounter this sentence: “There is, I know, loneliness in this world so great that you can see IT and hear IT in the ticking hand of a watch.” Christopher forges a perfect union between these two poles, working alchemical magic by transforming absurdity into the realest cold facts of life and death.

Another thing to note with this book is the breadth of its experimentation. A quartet of stories is told via receipts, overdue library book notices, and police bulletins, with lengthy titles as setups. One story appears to have been dictated, but it becomes surreally difficult to separate narrative and commentary. The title to another story, “The Living,” pays homage to Joyce’s “The Dead.” As far as homages go, however, Christopher’s last line might be even better: “I could see their mouths opening greedily for the sweet, hot milk of life, and I was no longer afraid.”

But, for all his willingness to push boundaries, Christopher is dedicated to telling a good story. My favorite, “Legs,” is about nothing more than a guy getting into a sketchy cab and talking to the driver. They commiserate about love gone wrong. The passenger asks about the bullet holes in the seat back. The cabbie (a woman) tells him a story. Then the passenger tells the cabbie a story. She gives him advice. They get closer to his destination. She asks him:

“You fingering my bullet holes now?”

“Yes, I am.”

“Keep doing it,” she says, “I’m almost there. We both almost there.”

These six short pages contain everything there is to say about love and what it does to people. I took photos of passages from “Legs” with my phone, and I’ve been sending them to anyone who reads fiction.

It feels strange to celebrate a great writer whose work you discover only after they’ve died. Peter Christopher taught creative writing for years at different universities, winning awards for his teaching and his writing. He published one book of stories, Campfires of the Dead, more than thirty years ago and it went out of print. He died in 2008 at the age of fifty-two. Campfires of the Dead and The Living contains the stories in that first book in their entirety, plus everything published posthumously. It’s bitter that we won’t get more. But what we have is sweeter than you can imagine.

Conor Hultman lives in Oxford, Mississippi.

More Reviews