In this edition of “I Wake Up Streaming,” novelist William Boyle rounds up his top streaming picks for the month of November. The column’s name is a play on the 1941 film I Wake Up Screaming, starring Betty Grable, Victor Mature, and Carole Landis. While the film’s title hits a pleasing note of terror and despair, changing that one letter speaks to the joy of discovering new films and rediscovering old favorites, as well as the panic that comes with being overwhelmed by options.

Sly (Netflix)

Sylvester Stallone and Bruce Springsteen are forever linked in my mind because of 1997’s Cop Land, so it’s interesting that director Thom Zimny—who has directed several Springsteen docs in recent years as well as Springsteen on Broadway—helmed Sly. I was already a longtime Stallone fan when Cop Land came out, having grown up on the Rocky and Rambo movies and seen just about everything else Stallone starred in. Cop Land—where Stallone’s Sherriff Freddy Heflin listens to The River on vinyl—marked my conversion as a Springsteen fan. I’d misheard and misinterpreted him for years before that, which is to say nothing of the fact that I hadn’t dug very deep beyond the radio hits. In any case, I went straight to Kim’s Mondo Underground after seeing Cop Land and picked up that scratchy old double vinyl LP of The River and started down a long, good road I’m still travelling today. I’ve been on an even longer and windier road with Stallone. As subjects, Stallone and Springsteen are thoughtful, reflective, self-aggrandizing, and funny in a lot of the same ways, and Zimny is great at capturing what makes them unique and important artists. Sly is framed as a conversation with Stallone, as he gets ready to move with his family from California to Florida. He’s looking back, analyzing, dissecting, and talking about regrets in a frank and honest way. I’d say the documentary borders on hagiography, but that’s selling it short. It’s more of a portrait of Stallone, who—contrary to his persona as gruff and monosyllabic—is a terrific talker. We hear him discuss his early years—born in Hell’s Kitchen, taken to Maryland by his dad, stumbling into a life surrounded by horses and starting to get good at playing polo, suddenly infected by the acting and writing bugs. Despite some sketchy entries in his filmography, most folks know what Stallone is capable of as an actor (we’ve seen him at his best in movies like Rocky, Cop Land, Rocky Balboa, and Creed), but he’s still vastly underappreciated as a writer. The doc, thankfully, focuses quite a bit on this aspect of his career. He started writing because he knew the only way to get roles he sought was to write them for himself. He was driven and disciplined. Attention mostly gets paid to his work in the ’70s and early ’80s—his breakout role in The Lords of Flatbush, Rocky, F.I.S.T., Paradise Alley, Rocky II, Rocky III, First Blood, and Rocky IV (he wrote or co-wrote the scripts for all of these except The Lords of Flatbush)—though we do delve into the ’90s and ’00s to examine the first Rocky sequel to fail, Rocky V, his “comeback” performance in Cop Land, and the movie that Stallone calls his greatest achievement, Rocky Balboa (my second favorite of the franchise). There’s also some conversation about 2010’s The Expendables, his third successful franchise, envisioned as an opportunity for old action stars to shine in the way that old rock stars often do. His action career is glossed over in a pretty general way, featuring footage from some of the films but not many specific discussions. We get an aside on his failed foray into comedy, a product of his rivalry with Arnold Schwarzenegger, who was much more of a natural comedian. We also get a sense that Stallone knew how to give an audience what they wanted—he knew how to write hits—and he was very good at learning from his mistakes. It’s easy to feel disappointed that certain films aren’t covered. Creed, for which he received an Oscar nomination for supporting actor, doesn’t even rate a mention, but one suspects that’s because he’s pissed about having been excluded from Creed III. His work as a director is largely underdiscussed, and I—selfishly—would’ve loved to see him expound on an ambitious bomb like Staying Alive instead of wasting breath on Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot. Anyhow, Sly is ultimately more about listening to Stallone wax philosophical about life and art. Central to the proceedings is a fraught relationship with his father—a brutal, difficult, and jealous man Stallone’s never been able to shake. Two of the doc’s most riveting moments involve Stallone processing trauma he faced at the hands of his old man. In one of those moments, he recalls improvising during a scene with Burgess Meredith’s Mickey in Rocky, saying all the things he’d always wanted to say to his father. In another, he screens one of his favorite films, The Lion in Winter, for Zimny, relating it to his relationship with his father. Back in high school, one of my favorite English teachers, Mr. MacLarty, a retired cop who loved Thomas Wolfe, used to say, “Sylvester Stallone was an artist in the ’70s.” I think I adopted that attitude for a long time, too, believing—even though I remained a fan—that he’d somehow sold out. After the failure of 1978 passion project Paradise Alley (which I absolutely love), he turned to Rocky sequels and—with the success of First Blood—became an unexpected action star. In retrospect, though, his arc is far more complicated than it at first seems. Everything he did was a choice. “I’m in the hope business,” he says at the end of Sly. “And I just hate sad endings. Sorry. Shoot me.” Cue Tom Waits’s “Come On Up to the House.” I wept. I’ve been watching and engaging with Stallone’s work for as long as I can remember. When I was a kid, I told my mom and stepdad I wanted to write screenplays, and they bought me a bound copy of the script for Rocky. I studied that thing. I’m still studying Stallone. This year alone, I’ve rewatched twenty-four of his movies. If you can’t get enough of him talking, this pairs well with John Herzfeld’s The Making of Rocky vs. Drago by Sylvester Stallone, a doc shot on an iPhone during the pandemic about Stallone reediting Rocky IV (it’s available for free on YouTube). And many of his films are currently streaming—I followed this up by rewatching Cop Land, which is also on Netflix, in which Stallone gives arguably his best performance as the half-deaf sheriff of a New Jersey town infested with corrupt New York City cops. Across from actors like Ray Liotta, Harvey Keitel, Robert De Niro, and Annabella Sciorra, you see what he can do with all that emotion he carries.

Uncle Joe Shannon (Prime Video and MGM+)

RIP Burt Young. Talia Shire gets mentioned in Sly, but Burt Young unfortunately doesn’t. We see him, of course, but Stallone doesn’t talk about casting him or their long collaboration. Because Young’s Paulie is capable of such cruelty, I hesitate to say that he’s the heart of the Rocky movies, but he’s certainly a major part of what makes them work so well (like Stallone, he gives a particularly moving performance in Rocky Balboa). Even though Young’s been one of my favorite actors for most of my movie-loving life, I’d somehow never seen or even heard of 1978’s Uncle Joe Shannon until recently. I can’t say for sure, but I feel almost certain that this must’ve been greenlit in the wake of the massive success of Rocky. (In that respect, it serves as an interesting companion to Paradise Alley.) It’s hard to imagine a scenario where it would’ve otherwise gotten made. Only in the ’70s, man. Young wrote it and stars as Joe Shannon, a famous trumpet player who loses his wife and son in a fire, hits rock bottom, and then rediscovers purpose in life through his friendship with Robbie, the sick, abandoned son of a former girlfriend. It’s a beautiful performance by Young, all heavy heartbreak and decay and slow-burning hope—no one can quite pull those things off like him. Tone-wise, the movie hits like a noir-tinged combination of Chet Baker and Heartattack and Vine–era Tom Waits with a bit of Bad Santa, Paper Moon, and Manchester by the Sea mixed in there. The Bill Conti score drives the whole thing. Uncle Joe Shannon is loose and shaggy, a melancholy bawler that veers into hangout movie territory. Right up my goddamn alley.

Lynch/Oz (Criterion Channel)

Early one Saturday when I was twelve years old, I rented David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. I’m not being hyperbolic when I say it changed my life, literally altered the way I saw the world. I’ve always thought about that day in terms of The Wizard of Oz. When I left my apartment later that afternoon and went to church with my mom and grandparents, it was very much akin to the switch from dusty sepia to vivid color that Dorothy goes through when she’s transported from Kansas to Oz. The world was one way and then it was another. I was a kid and then I wasn’t. I felt as if I’d seen behind the curtain. A Lynch movie can have that impact. Not long afterwards, Twin Peaks and Wild at Heart—both of which feature overt nods to The Wizard of Oz—consumed me. Alexandre O. Philippe’s Lynch/Oz traces the impact The Wizard of Oz has had on Lynch. It’s a movie “he thinks about every day,” and we explore ways its influence has filtered into his work. The documentary is structured as a series of video essays, with contributions from one film critic, Amy Nicholson, and several filmmakers—Rodney Ascher, John Waters, Karyn Kusama, Aaron Moorhead, Justin Benson, and David Lowery. Some of the segments are stronger than others—Kusama’s is the best and most illuminating—but the whole thing is a ton of fun.

Early one Saturday when I was twelve years old, I rented David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. I’m not being hyperbolic when I say it changed my life, literally altered the way I saw the world. I’ve always thought about that day in terms of The Wizard of Oz. When I left my apartment later that afternoon and went to church with my mom and grandparents, it was very much akin to the switch from dusty sepia to vivid color that Dorothy goes through when she’s transported from Kansas to Oz. The world was one way and then it was another. I was a kid and then I wasn’t. I felt as if I’d seen behind the curtain. A Lynch movie can have that impact. Not long afterwards, Twin Peaks and Wild at Heart—both of which feature overt nods to The Wizard of Oz—consumed me. Alexandre O. Philippe’s Lynch/Oz traces the impact The Wizard of Oz has had on Lynch. It’s a movie “he thinks about every day,” and we explore ways its influence has filtered into his work. The documentary is structured as a series of video essays, with contributions from one film critic, Amy Nicholson, and several filmmakers—Rodney Ascher, John Waters, Karyn Kusama, Aaron Moorhead, Justin Benson, and David Lowery. Some of the segments are stronger than others—Kusama’s is the best and most illuminating—but the whole thing is a ton of fun.

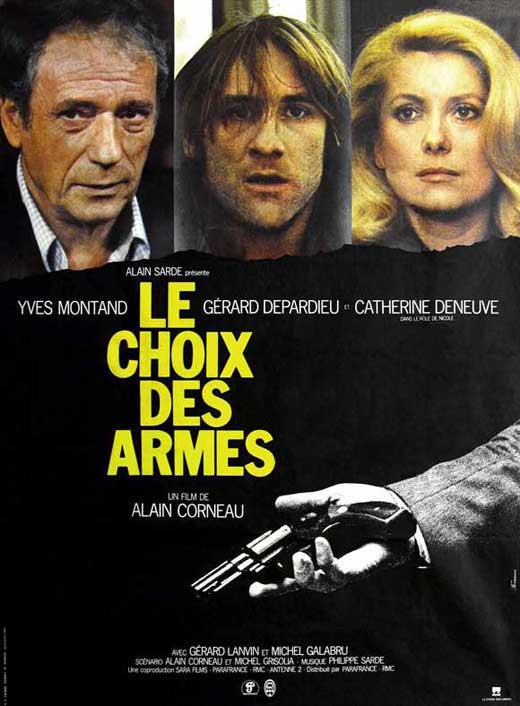

Choice of Arms (Kanopy)

A revelatory first-time watch. Alain Corneau’s 1981 follow-up to Série Noire, his masterful adaptation of Jim Thompson’s A Hell of a Woman. Just very much my thing. A sprawling but small-scale crime drama about fate, mercy, and bad luck. Controlled, melancholy, full of yearning. Yves Montand is excellent as a gangster gone straight whose life unravels when his brother, having just escaped prison and fallen quickly into a bad situation, shows up bleeding at his door with a tagalong goon. Gérard Depardieu is Mickey, the goon, a dumb bad guy with heart, occasionally unhinged but capable of tenderness. Catherine Deneuve is at her most stunning as Montand’s wife. The cops are all shitheads and morons. Everything comes crashing down, of course. A beautiful movie.

A revelatory first-time watch. Alain Corneau’s 1981 follow-up to Série Noire, his masterful adaptation of Jim Thompson’s A Hell of a Woman. Just very much my thing. A sprawling but small-scale crime drama about fate, mercy, and bad luck. Controlled, melancholy, full of yearning. Yves Montand is excellent as a gangster gone straight whose life unravels when his brother, having just escaped prison and fallen quickly into a bad situation, shows up bleeding at his door with a tagalong goon. Gérard Depardieu is Mickey, the goon, a dumb bad guy with heart, occasionally unhinged but capable of tenderness. Catherine Deneuve is at her most stunning as Montand’s wife. The cops are all shitheads and morons. Everything comes crashing down, of course. A beautiful movie.

William Boyle is the author of the novels Gravesend, The Lonely Witness, A Friend Is a Gift You Give Yourself, City of Margins, and Shoot the Moonlight Out. His novella Everything Is Broken was published in Southwest Review Volume 104, numbers 1–4. His website is williammichaelboyle.com.

Illustration: Jess Rotter