Pure, Entertaining Thinking

Reviews

By Sam Hockley-Smith

In a piece entitled “Back In Black,” music writer Dave Marsh attempts to describe the state of play in the U.S. circa 1991. He writes about the Gulf War. He writes about George Bush hiring former Florida governor Robert Martinez to serve as “drug czar.” He writes about the attempted censorship of Metallica, N.W.A., and Robert Mapplethorpe. He writes about Aerosmith making a plainly anti-war remark at the Grammys. Jeb Bush’s name even appears in a parenthetical.

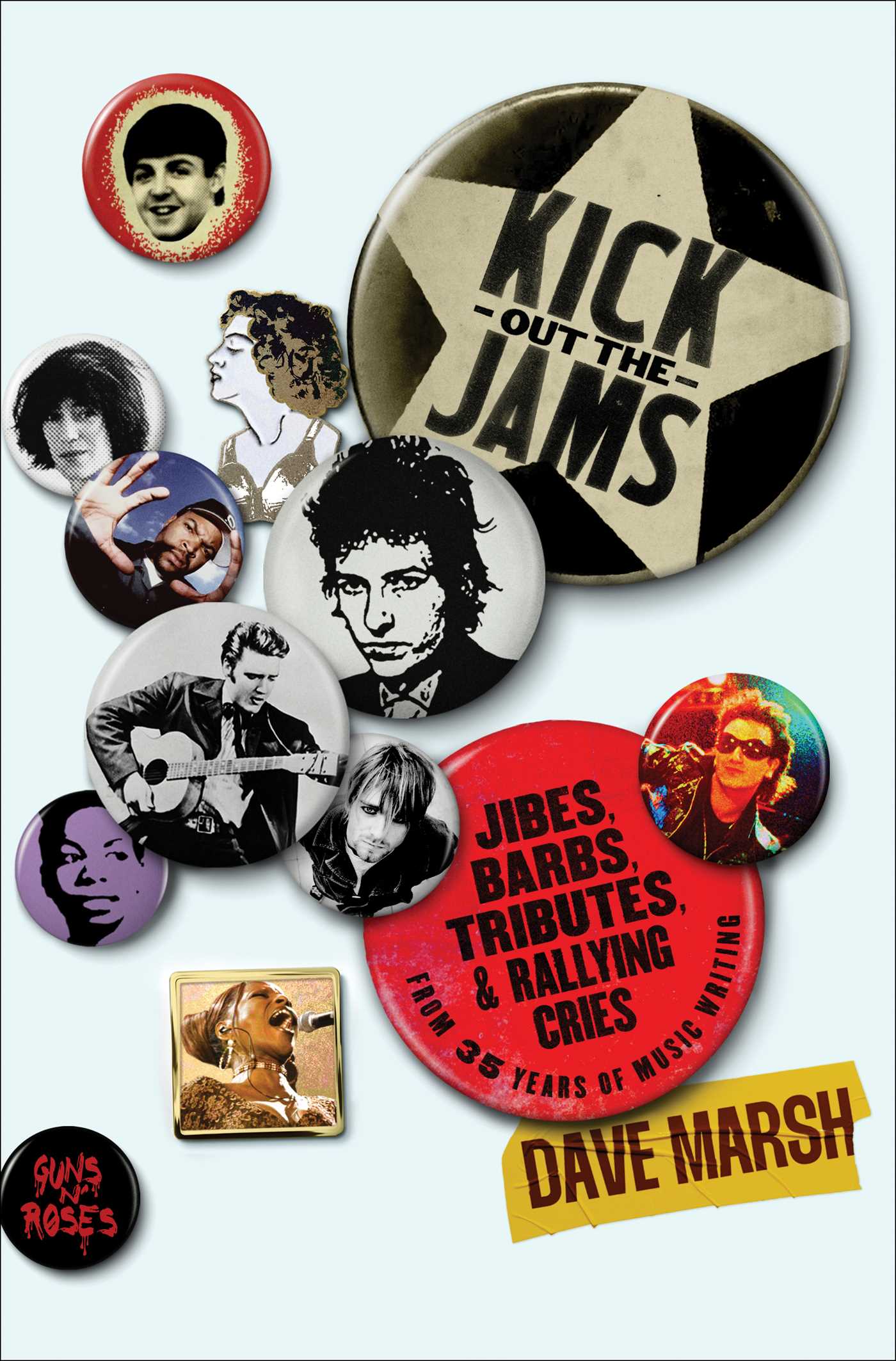

A little later in Kick Out the Jams: Jibes, Barbs, Tributes, and Rallying Cries From 25 Years of Music Writing, a new collection of Marsh’s writing from the ’80s through 2017, we’re treated to a one-page chapter, also from 1991. The top half of the page is occupied by a lengthy quote from Axl Rose, who assumes Marsh will take offense to the Guns N’ Roses song “One in a Million.” Which Marsh of course does because “One in a Million” is a racist, homophobic, xenophobic song that casts Rose as a scared country kid contending with the big city the only way he knows how: by feeling threatened by everyone who is even slightly different from him. Marsh’s response is concise and plainly correct. He wonders why Rose is conflating fear of violence with fear of other races, and he leaves it at that.

Little has changed since 1991. The world is better in a couple ways, worse in a lot more. But if the whole protracted written scuffle between Marsh and Rose happened today, it would have occurred on Twitter. Consequently, both men would probably have come out of it much worse for the wear, with no point being understood on either side. It also would have all happened in about forty-five seconds and then been entirely forgotten in ninety. So yes: the shape of the world is the same, but sort of worse. Our problems remain the same, but sort of worse. The end of the world is still looming; it’s just a lot closer than it used to be.

You’d think that, amidst all this worsening, music writing would have trucked along as normal. We’re humans! We love reading about famous people! We love hearing music that connects to our emotional core and shifts our entire perspective! Music’s power to heal is so widely accepted that even saying so is a cliché. But music criticism—what we want from it, what it’s supposed to do, how people interact with it—is now rarely allowed to be as loose and real as Dave Marsh’s writing. What happened?

Music writing has been subsumed into the celebrity culture it helps prop up. What was once a form of expression predicated on the concept of exploring the clash between art as perceived by the artist and art as perceived by an audience has now become a blatant PR vehicle. That is, it’s become a communication mode for artists to explain what they want to explain without much pushback. This isn’t necessarily as dire as it seems (though it’s not great). Culture writing, especially when it includes celebrities, is PR by nature. It always has been. But good work still comes from that arrangement. Compelling personalities are compelling personalities, and some art can touch us in such a deep way that any sentence scrap or insight into its making becomes almost as essential as the art itself. At its best, music writing is an exploration of a deep love for the art made by its subject, even when that subject fails its listener. That last bit, it turns out, is pretty important and may be more prevalent than we initially assumed. How do we contend with art when it fails us? Does it owe us something? Do we owe it?

Marsh pursues this line of questioning in a significant portion of the material collected in Kick Out the Jams, which mostly pulls pieces from his newsletter Rock & Rap Confidential, as well as Addicted to Noise, CounterPunch, and a smattering of other outlets he was writing for between 1984-2017. And he does so with a looseness and conversational tone that consistently pulls the reader in. Whether he’s excavating the revolutionary importance of the MC5, or, like every other white critic, writing about Elvis, Marsh’s work feels fresh.

All too often, music criticism can feel like the critic has been sent as some sort of emissary or representative to submit a GRAND OPINION. This is largely a misguided understanding of the unique dynamic between artist and critic, which places outsize importance on both figures without considering the inherent subjectivity of art when it is consumed by an individual. In other words, something that means a lot to you might mean nothing to me. Neither of us is wrong, and we’re both right.

The writing collected in Jams dates mostly from a pre-internet era. Back then, you pretty much had one way to get your opinion out into the world: write it down and hope that some people read it. Marsh has that last part down pat. His writing, which is moral without being preachy, which expects the best of his subjects but doesn’t take out his personal grievances on them, is generous. Even that brief Axl Rose piece, which certainly could have been much harsher, ends with a plea: “So thanks for the mention, and I hope that someday we get to finish the discussion, face to face.” Marsh doesn’t back down, but he shows real kindness even when taking someone to task. That ethical stance probably explains why Jams is being pitched as a sort of corrective. In his intro, co-editor Daniel Wolff asks a version of the question: How did one of the founders of Creem, one of the major writers of Rolling Stone at its most influential, become overlooked?

Readers may or may not find an answer in this book, so allow me to throw a theory out there. Marsh helped define music criticism. He’s written twenty-two books, including multiple biographies of Bruce Springsteen. He’s a radio host on SiriusXM. He’s a major player in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. He is not so much overlooked as properly comfortable, maybe even happy. There’s a tendency to romanticize the lives of music writers (thanks Almost Famous!), but a quick glance into the life of, say, Lester Bangs, reveals that his was a largely thankless career built on cloaking genuinely valuable perceptions in shock and exaggerated emotion. How much should any of us be willing to suffer for fame? In a perfect world, not at all.

Even when it’s academic, music criticism is—and always has been—a lot like wrestling. Marsh’s ability to write with personality without letting that personality overtake his subjects—or overtake his larger thesis in any given piece—means he’d make a terrible professional wrestler. He wouldn’t be jumping around yelling. He wouldn’t be pulling sketchy moves like hitting other guys in the back of the legs with a folding chair or whatever. He’d play it by the book. Bangs and Lou Reed had an iconic rivalry that oscillated between pure vitriol and intellectual barbs that felt like performance art. Marsh, on the other hand, has conviction. And conviction isn’t nothing. In fact, it’s the reason why so much of Marsh’s writing feels relevant today.

This is no small feat. Music writing is, by nature, of its time. Pieces become out of date mere days or weeks after they’re published, and much of the music that appears in Jams has long been institutionalized, canonized, and litigated to death. It’s Marsh’s willingness to go out on a limb, get ultra-granular, or zoom way out to reveal the interplay between popular music and politics whenever the occasion calls for it that keeps his writing contemporary. Every page of Jams—from the intro through the afterword from The Who’s Pete Townshend—has something to tell us about Marsh’s humanity. He’s rarely the subject of his own writing, but his POV is very strong. He believes in art. He believes in goodness. He believes in humanity. His presence is always felt, whether he explicitly references himself in his writing or not.

In 1993, Marsh’s stepdaughter died from sarcoma, a rare form of cancer. He mentions her death in a few pieces, including one about folk musician Jimmy LaFave, who was dying of sarcoma when Marsh profiled him, and another elegiac piece in which Marsh and his family and friends put together a mixtape for his stepdaughter’s funeral. But her death hangs over the writing from this era that doesn’t even mention that event. It’s this willingness to fold music criticism into real life that forms the book’s backbone. All too often, criticism is conflated with journalism, as if our personal lives and experiences have no place in a supposedly objective story we’re trying to tell. Perhaps this is also why Marsh, despite being a major figure in the music industry, is deemed “forgotten.” His generosity of spirit means his pieces acknowledge the messiness of life—how a bad day can color your opinion of a song, or a good day can make music you used to think was trash actually sound good. He accepts that our lives are fundamentally inseparable from the art we enjoy (or really, really, don’t enjoy), and works from that baseline. He may not be infallible, but who is?

Nevertheless, you could view Jams as a sort of corrective to the staid opinions that populate so much institutional music writing. But I’m not sure it does that, nor am I sure that it actually needs to. The earlier, pre-internet, pieces in the book feel almost quaint. They’re enjoyable to read, and it’s nice to have them preserved in a book as opposed to relegated to the magazine collector corner of eBay. Still, they’re often minor by design. They feel like they’re filling in the gaps between the Big Statements of the day and the established facts of music in general. By the same token, this casualness is what makes the book so inherently readable. You’re going to feel inspired to listen to the music Marsh writes about, largely because he writes about it with such genuine passion. Music criticism doesn’t need to be definitive. It just has to be fun (remember fun?) to read.

Crucially, “fun to read” does not have to mean “fun in tone” or “about fun things.” It just needs to articulate a perspective that hasn’t been echoed and repeated a hundred million times. Throughout Kick out the Jams, Marsh repeatedly pulls epiphanies from ethically murky moments. Writing about Eminem’s star turn in 8 Mile, he examines the contradictions between normal life and the life of an artist. Rather than provide faux answers as to which life is “right,” or write a standard review of the film, Marsh digs down to the core. “Eminem says the movie’s message is that ‘no matter whether you come from the north side or the south side [of 8 Mile Road] you can break outta that,’ if ‘your mentality is right and your drive is right.’ But he’s wrong,” Marsh writes. “The film actually shows that in a world where everyone is trapped, including prep school kids, the only way out involves using your individual drive and vision to tell the painful truth—it’s not identity of any kind that can’t be faked, but emotional authenticity.”

Later in the essay, Marsh dramatically reinterprets the climactic rap battle in which Eminem’s character leans into his “trailer trash” past. He argues that Eminem isn’t proving his worth as a white artist engaging in a Black art form. Instead, he’s observing how he’s caught in tug-of-war between race solidarity and class solidarity. Marsh makes this point quickly, dispenses with the extraneous background detail, then ends the piece on an uncertain note that echoes the film’s discomfort with the trappings of fame and how even morsels of it can quickly subvert who you think you are.

Selecting highlights from a book chock full of them has proven to be an interesting process. It’s helped clarify for me what makes Marsh so inherently readable: his honesty, his brevity, his ability to understand when to leave out excess information in favor of voice or personal anecdote. It’s why Marsh is able to make well-worn subjects seem fresh and full of life, even though you’ve probably already read about virtually every artist mentioned in this book. Elvis. Nirvana. Springsteen. Eminem. Neil Young. These are well-worn subjects. Yet Marsh’s genuine love for and good faith in all artists—even the ones he maybe hates musically or personally—shines through, pointing to an alternate world. There, music writing is not dictated by SEO grabs, artist access, or nervous editors. There, music writing is a form of pure, entertaining thinking.

Sam Hockley-Smith is a writer, editor, and radio host based in Los Angeles. His work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, the FADER, Pitchfork, NPR, SSENSE, Bandcamp, Vulture, and more. His radio show, New Environments, airs monthly on Dublab. He spends his spare time reading.

More Reviews