Zonas de sacrificio | An Interview with Bruno Lloret

Interviews

By Ellen Jones

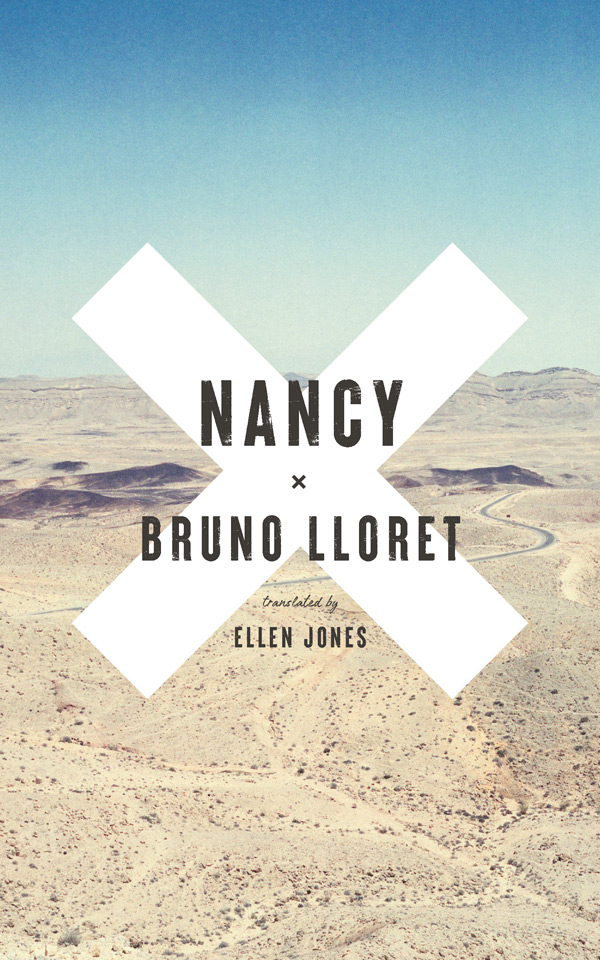

Bruno Lloret’s debut novel Nancy may be a slim volume, but it’s full of ideas. It takes in the ravaging effects of capitalism, environmental collapse, poverty, religion, and domestic violence. It is also a moving account of loneliness, grief, and the endurance of physical pain, shot through with unexpected black humor.

Dying of cancer, abandoned by her alcoholic husband, Nancy tells the story of her childhood and adolescence in Ch, a miserable port town in Chile’s desert north. After the disappearance of her older brother Patricio, her family begins to fall apart: her mother runs off with her abusive lover and her father converts to Mormonism. When not at school, Nancy spends her time having furtive sex with a Romany man named Jesulé and escaping to the beach with a group of Americans who film girls in their bikinis while they take cocaine and masturbate.

Bruno’s spare, poetic prose is interspersed with black crosses that slow our reading down, create elusive shapes on the page, and continuously remind us of the narrator’s mortality and of the conflicted role religious faith plays in her life. As translator, I tried to approach Nancy as prose poetry, paying close attention to the text’s rhythm, sound, and spacing.

On a long-overdue transatlantic Zoom, I spoke to Bruno about Nancy, geopolitics, the Bible, and nineties telenovelas.

Ellen Jones: There’s a memorable, very disturbing scene in Nancy in which a virus races through the local population of factory-farmed pigs and huge numbers have to be slaughtered, leaving whole communities destitute. I can’t help but reflect differently on that scene now, after having lived through a year of the COVID-19 pandemic. I wanted to ask you about the novel’s reflections on environmental destruction. We know it’s set in the near future, and there’s a pervasive sense that the landscape—just like Nancy’s body—is sickening, failing. Would it be useful to understand Nancy in relation to eco-literature?

Bruno Lloret: This was something that actually happened in a town in the north of Chile—an outbreak of swine flu meant something like sixteen thousand pigs were slaughtered and then burned to avoid the virus spreading. So that episode was based on real events. That said, it’s not the only thing of this kind that goes on in the novel. Pretty much from the 60s onwards in Chile, experts—let’s say engineers or government ministers—have decided which areas of the country they are prepared to sacrifice. That’s literally their name for certain areas; they call them zonas de sacrificio. And it’s really interesting because the Bible is full of sacrifices—to immolate your son or a ram, say, establishes a relationship with God.

It’s also interesting that the idea of ecology—of nature as a kind of harmonious machine—is really modern. It’s popular because the idea that nature is somehow harmonious reassures us, for instance, that in the future, when we humans have disappeared, the earth will once again find its intrinsic harmony. But if we look at what geologists and biologists are saying, it’s clear that nature is not predictable at all. It’s not harmonious. This is a human projection, because it allows us to think that we can predict or create some sort of eco-machine version of the earth, one that will allow us to sustain our way of living. I think this is highly delusional and really super-arrogant. So, in a sense, Nancy imagines the near future but also how, even now, parts of Chile and Latin America, as well as certain areas of Asia and Africa, have become huge “sacrifice zones.” For instance, Canada is a huge power in the Southern Hemisphere. They project this image of a harmonious, beautiful, pure landscape—they have clear lakes, beautiful mountains, all the forests—but behind that projection they are destroying other landscapes.

EJ: I just watched a great documentary about Spanish investment in clean energy on the south coast of Oaxaca. They built a huge wind farm that, ironically, has destroyed the local fishing communities and left the indigenous people impoverished. It sounds a lot like what you’re calling a “sacrifice zone.”

BL: Yes. It’s interesting because ecology and human rights—even though I firmly believe in both—are used by highly developed countries to control and teach the rest of the world how to behave. And if we consider the Brazilian approach to this situation, for instance—they say, “We have the right, like Europe did in the 18th century, to clear our forests and become an industrial power.” In a horrible sense, they have a point, you know? As far as Nancy is concerned, it’s a novel that’s in part about religion, which is a good way to explore how humans interpret what’s going on in nature. The scene with the pigs is based on reality but I also wanted to play with questions like: is this divine punishment or is this the result of human actions?

EJ: Speaking of religion, a major storyline is that Nancy’s father converts to Mormonism, and then she does too, although without much conviction. But each chapter of the novel also begins with a passage from the Bible, and there is often a biblical cast to the language. Can tell us more about how a religious style informs your novel?

BL: Yes. In contrast to the 18th- and 19th-century tradition of realist novels, I’ve always found it fascinating how the Bible and other premodern books don’t usually care much about fluency of style, nor do they feel the need to present a lot of context. That’s why I love the Book of Job, because in the second paragraph so many things happen to Job that if it were a TV show it would probably take up about six seasons. The priority is not to entertain or to create something aesthetically pleasing. I love how it has this rustic and really straightforward way of telling things.

EJ: That makes me think of the beginning of Nancy, where in the space of one sentence—about 12 words—she gets married, moves to Bolivia, and then moves back to Chile.

BL: Exactly, exactly. It’s like Yuri Herrera’s novel [Signs Preceding the End of the World, trans. by Lisa Dillman] in, say, two paragraphs. And yes, stylistically speaking, in Nancy the Bible, which is really not a symmetrical book, is very important. The Book of Genesis covers the first two thousand years on earth whereas the New Testament covers just thirty-three years, focusing on the last three years in the life of Jesus. I find this acceleration interesting and really refreshing. I found the same thing in the work of Roberto Bolaño when I was younger. His prose has a sense of freshness; he’s able to just tell things straightforwardly. Sometimes I feel like rejecting literature that knows it is beautiful and takes the time to show how beautiful it is. So, stylistically speaking, that’s the main biblical influence on Nancy: a kind of blunt narration that these days I think is quite refreshing.

EJ: I’m going to ask you something I’m sure you’ve been asked a hundred times. One of the most immediately recognizable and memorable things about Nancy is its visual appearance. You’ve said that the Xs ended up coming to stand in for other forms of punctuation in the novel, but they don’t exactly have a grammatical logic, do they? That said, they definitely have symbolic significance in the novel, insofar as Nancy is partly about mortality and partly about faith, or lack of it. Can you tell us how you arrived at these crosses and the logic that informs them?

BL: Originally the Xs were not even Xs. They were em dashes. Then, because I really love the way Kafka’s novels uses brackets, < > , in his novels to indicate dialogue in the middle of a really dense paragraph, I started to use brackets instead. But I realised that when two sentences run together the brackets create an X, you see? ><. So originally the X was kind of a coincidence; a happy accident. Then before long the tiny gap between the brackets, that kind of asymptote, began to really annoy me, so I moved to actual Xs.

Later I became aware of their graphic potential and started to experiment. For example, there’s a moment when Nancy is in Bolivia and she meets this shepherd, and they talk about the clouds and their shadows. It’s a moment of quietness and contemplation. I’ve been there, to that part of Bolivia, and the sky and the sun are just amazing, surreal. It’s like another world. I wanted to create a safe place for the character in that moment, so I started to experiment with the Xs and the results were so satisfactory that I kept using them, not only graphically but also to make the language interact somehow with the landscape.

EJ: Now that you mention it, that scene with the clouds—when you see it on the page, the Xs almost create an image, because there are very short phrases buried in this sky of Xs, almost like they’re clouds. I mean, you’re almost approaching concrete poetry there, right?

BL: Right, but also . . . I don’t know if you’re aware of what meditation practice teaches you: the mind as language. In a sense it’s a beautiful kind of coincidence, the idea of these words describing the clouds, which are passing as you read them, evaporating, you know, “like words or cigarettes,” which is literally a line in the novel.

So yes, the Xs are like concrete poetry but they also create a lot of connections between different textual levels, which is not something that was really planned. For instance, they link together the visual/graphic with the oral, creating space and texture on the page, even evoking images, but also inserting white noise between sentences, suggesting unheard voices, unspoken thoughts. The clouds are also depicted in this graphic way so it’s concrete poetry on some level. But the clouds are also like words that come and go. And also we have to remember that all of this is happening in Nancy’s mind while she’s dying.

The other important thing about the Xs was to start to create a rhythm. They helped me be much more relaxed and loose with the idea of copy-pasting sections, creating an assemblage of different moments or scenes. So in that sense they became sort of a rhythmic but also a visual way of connecting different scenes. When I was editing the novel for the first time, the editors [Francisco Ovando and Galo Ghigliotto at Cuneta] started to propose certain uses of the Xs because even though there’s not a set of rules, after some time spent reading the novel you start to get a feeling for their use. Did you ever get that feeling?

EJ: Actually, just the other day I was comparing my English version and your Spanish version and on the very first page there’s a stark difference in the way we use the crosses. Which has to do, of course, with the fact that English has different rhythms and also makes different shapes on the page. I also remember that on pages where there’s a heavier use of Xs I started to feel strongly that they should look a certain way—that words should be held safely within this framework or structure of crosses rather than spilling off to one side, for instance.

BL: Right. In the end the most important thing about the Xs is that they bring the reader to a different type of attention. They help you to develop a pattern of reading when you first start the book, and after that the idea is to allow every reader to create their own theories. For example, somebody once said to me, “So, in such-and-such a scene, Nancy mentions two dogs or two sheep and right after that there are two crosses.” So this person believed there was a numerical correlation between certain objects or beings in the novel, and started counting the Xs on certain pages to see if the theory fit. And this is interesting because in a way it’s really biblical, this kind of exegesis, trying to figure out different layers of meaning like people did with the Bible. So that was the final spirit of the Xs: to grab readers’ attention and suggest to them that they engage in a more dynamic way with the novel.

EJ: It’s a kind of active reading isn’t it, where you’re in some sense creating the text. It’s not the author who’s doing it all for you.

BL: I guess it goes against this idea of the transparency of language in novels in general. I’ve read some novels super-fast because the language is so transparent that you kind of process the data and see the images really quickly. Particularly our generation, people that grew up with images, we’re really good at imagining things. Perhaps that’s one of the main reasons why in no novel today do you find a long description of what a family’s living room looks like. That’s really characteristic of the 19th-century novel. And I think this difference is clearly to do with the insane number of images we have in our brains these days.

EJ: Right, that nothing is ever out of our reach. If I want to know what the Bolivian altiplano looks like, I can find out in three seconds by googling. I don’t need somebody to describe it for me verbally.

BL: Right. Nancy doesn’t stop to elaborate on really complicated landscapes. She doesn’t over-explain anything. It’s a really minimalist approach.

EJ: Actually, one of the interesting and most challenging things about translating the novel was precisely that reluctance to explain, that minimalist style. And picking up on something you just said, I wanted to ask you about voice in the novel. I think that in Nancy there’s a tension between the novel as a written artifact—because the crosses give the novel this visual life on the page—and its oral life, which is quite different. Notably, Jesulé speaks in a very marked variant of Chilean Spanish—another thing that was particularly difficult to recreate in English! I wanted to ask you about that tension between the book as something that’s written and something that has a sound or a voice.

BL: Yes, that’s a great question. There’s an amazing documentary, really important for the novel, called Don Roberto’s Shadow, by Juan Diego Spoerer and Håkan Engström. It’s about the keeper of a saltpeter mine who lives in an abandoned adobe building that was used as a torture facility during the dictatorship. At one point the cameraman asks him if he hears things—entities or ghosts—in this place. He says, “yes,” and the cameraman asks him who he thinks these people are, and Don Roberto’s explanation is beautiful. He says that the walls are made from mountain clay that, chemically speaking, has the same composition as the material you would use in an old-fashioned tape recorder. So all the horrible things that have happened in this place, all those voices, have literally been recorded in the adobe walls. Because voices are resonances or vibrations, material-mechanic expressions of thought. Nancy places a lot of emphasis on adobe, as well as on other desert materials, mountains, walls, abandoned iron constructions, even sand. Those materials are repositories for voices, and so is Nancy’s body—it’s a kind of resonance box, like in a guitar. Her body is a record of the scenes she has lived and the words she has spoken, and in turn the book itself is a record of those words, contaminated with Xs like her body is contaminated with cancerous cells. And so the book explores the parallels between landscapes, bodies, and texts.

EJ: That’s so interesting, the novel itself as a body that’s being invaded by this cancer, Nancy’s textual voice being contaminated by the Xs. I have one final question for you. Can you help readers locate the book in the context of other contemporary Chilean writing?

BL: Sometimes writers don’t like to talk about influences. I love to talk about my influences. But I’ll be honest: I don’t read much contemporary Chilean literature at all. Nancy has been compared a lot with a novel by Diego Zúñiga called Camanchaca, which is also about the desert and the north of Chile. But the other really important influence on Nancy is a series of telenovelas made by Vicente Sabatini, from the so-called golden age of Chilean telenovelas. One of them, Romané, was based in the north, in an industrial port, and it’s about a group of Romany people. All the actors were professional theatre actors—amazing. These telenovelas became so embedded in our collective memory that the way we perceive Romany people in Chile is thanks to this series—the stereotype of the “sexy gypsy,” for instance. The way Jesulé is depicted in Nancy has currency in Chile; I literally think readers will imagine specific actors from that time. Nancy, on the other hand, I prefer to think of as a collection of discursive strategies. For example, I have never thought about Nancy’s face, and that’s not a problem for me. I like to allow the reader to fill in those gaps and imagine the character.

EJ: You’re right, we have no idea what Nancy looks like! But it doesn’t matter, does it? As a reader, you just create her. You imagine.

BL: I think that’s how dreams work, too.

Bruno Lloret (Santiago de Chile, 1990) is a writer and researcher. He has published two novels: Nancy (Cuneta, Chile, 2015; Giramondo, Australia, 2020; DharmaBooks, Mexico, 2021; Two Lines Press, USA, 2021; Candaya, Spain, 2021) and Leña (Overol, Chile, 2018)

Ellen Jones is a literary translator from Spanish to English, an editor, and an occasional writer based in Mexico City. Her translation of Bruno Lloret’s Nancy is currently available from Giramondo Publishing and Two Lines Press.

More Interviews