Columns

music

The Guest List | Dummy

music

The Guest List | Wand

music

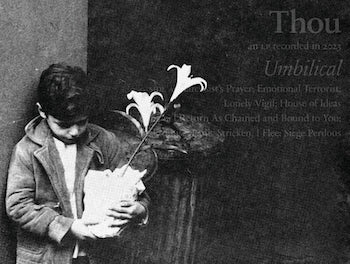

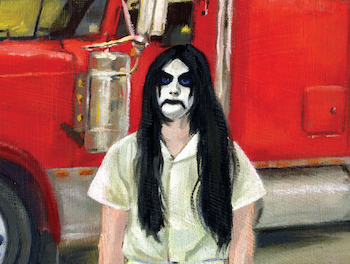

The Guest List | Thou

music

The Guest List | Dehd

music

The Guest List | Ratboys

music

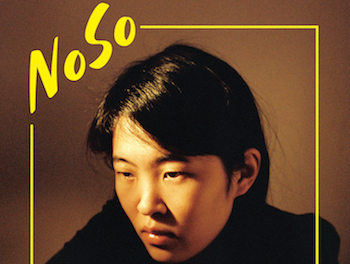

The Guest List | NoSo

sports